dokieli: decentralised authoring, annotations and social notifications

This article is superseded by Decentralised Authoring, Annotations and Notifications for a Read-Write Web with dokieli.

- Identifier

- https://csarven.ca/dokieli

- Notifications Inbox

- inbox/

- In Reply To

- LDOW2016 Call for Papers

- Published

- Modified

- License

- CC BY 4.0

Abstract

In this article we present an architecture for progressively enhanced user-facing linked data applications and demonstrate this architecture through an open source example implementation: dokieli. dokieli is a general purpose client-side application for document authoring, publication and interaction. Capabilities of the tool are enabled according to the needs and technical resources of the user. The editor is built on open Web standards and the documents are compliant with Linked Data best practices, allowing: decentralised storage and data ownership; fine-grained semantic structure through HTML+RDFa; direct in-browser editing from an LDP-based personal data store; social interactions with documents (such as annotations and replies), and notifications thereof. This article itself is a dokieli instance, available to interact with at https://csarven.ca/dokieli.

Keywords

Categories and Subject Descriptors

Introduction

When I saw the computer, I said, ‘at last we can escape from the prison of paper’, and that was what my whole hypertext idea was about in 1960 and since. Contrarily, what did the other people do, they imitated paper, which to me seems totally insane

- Ted Nelson [1].

Our aim is to create and enhance opportunities for open knowledge exchange. Ideas and the conversations around them take the form of prose, which is widely published on the Web, and our hope is to iterate towards unleashing greater utility of this kind of content, whilst retaining its accessibility.

A long-lasting system must be evolvable. It is difficult to predict which technologies will endure over time, however we take inspiration from the Evolution of the Web [2], and pursue features like simplicity, flexibility, decentralisation, interoperability, and tolerance.

We have combined commonplace online publishing practices with contemporary Web standards to create a novel architecture for user-facing, progressively enhanced Linked Data applications. Progressive enhancement is a paradigm for Web application development that emerged circa 2003. A progressively enhanced Web application focuses on the content, starting with semantic HTML markup, and gradually adding more advanced CSS and JavaScript features if the user’s browser permits. An experience may be immensely improved by these extra features, but they are not required in order to access the information on the page. At the time, this gave Web developers a mechanism to improve accessibility across devices and mitigate against constraints of outdated browsers. We are expanding on this concept from considering the users’ clients to also take into account users’ own servers or personal datastores if available.

We believe this has the potential to both proliferate high quality machine-readable data, and enhance human-friendly knowledge sharing on the Web. Our baseline technology of HTML+RDFa fosters accessibility by default, and serves as a foundation on which we can build layers of functionality until we reach the interactive social experiences that people expect from the Web today. This architecture is decentralised, affording users greater control of their data, and optionally enhanced through use of the Solid platform (described further in section 4.5).

We explore the feasibility of this architecture through an implementation, which serves as the focus of this article. dokieli is a client-side application for authoring, publishing and interaction with prose content. We discuss the problem space, existing standards and tools on which we have built, as well as specific implementation details of dokieli. Implementation is ongoing, and we conclude with lessons learnt so far and a discussion of the problems which remain to be solved.

Problem space

Our scope covers three primary areas: authoring and publication, annotation and social notifications, and multimodal semantic content and interactivity. We take a brief look at use cases from some existing, overlapping, work in these areas.

The W3C Social Web Working Group presents user stories for various common online social activities. Noting that all of these user stories are expected to work in a decentralised manner (with all participants using different technology stacks), we consider the use cases which involve creating and updating content which is intended to be shared with others; interacting with existing content; and content creators being notified when someone interacts with their content.

The W3C Web Annotation Working Group and Digital Publishing Interest Group put forward a set of use cases for annotation activities. One intuitive use case for annotation is commenting on a span of text (a reviewer annotates a sentence by suggesting that it needs citation).

The Linked Research initiative [3] takes a critical look at the current level of access to academic work, putting out a call for better presentation, discoverability and reuse of research objects. We keep in mind the proposed acid test [4] to verify the openness, accessibility, and flexibility of approaches to scholarly communication. This is intended to improve opportunities for knowledge acquisition and education through: fine-grained identification of arguments and concepts; linking for concept reuse and building information networks; embedding of machine-readable semantics for fast aggregation and remixing of work; interactive and executable interfaces for improved learnability.

These areas of interest cover anywhere from data-driven journalism, online news, scholarly articles and peer-reviews, to casual communication through blogging and social media, but the theme of widening participation through spreading of knowledge and ideas in accessible ways is central to our motivation.

We summarise these areas with a list of requirements that implementations of our architecture should meet.

- Requirements

-

- Publication and sharing of knowledge and ideas is encouraged with user friendly content creation interfaces.

- Discussion and commentary is promoted through integration of tools for social interaction and notification.

- Data is stored in a decentralised way, in a location that the creator controls.

- Data is loosely coupled with the applications used to create and view it, and machine-readable, so that it is reusable by other applications.

- Applications and data formats are progressively enhanced such that content is minimally accessible to users with different capabilities and technical resources.

Architecture

Articles are written to share knowledge. The architecture we have chosen enables this knowledge to be as widely accessible as possible; the capabilities of dokieli are designed such that they are enabled progressively and individually, according to the user’s needs and technical resources at the time. The most minimal tooling required to read content produced with dokieli is a command-line interface or Line Mode Browser. Given a modern Web browser, Linked Data tooling, or an LDP-compatible server, documents and data can be consumed, created, connected and manipulated in more powerful and visually appealing ways.

In this section we describe the existing standards and protocols which provide the building blocks for our architecture, and how these pieces fit together to make this approach possible.

Data format

The native serialisation for dokieli documents is HTML+RDFa. HTML enables human-readable articles by default; RDFa, which is particularly well suited to the longform content dokieli is used to create, augments the documents with a machine-readable structure. We consider content of a document to be of foremost importance, and RDFa allows authors to add semantic structure to their ideas inline. Alternative syntaxes such as Turtle, JSON-LD, and TriG may be embedded into HTML as raw data islands, though this causes unnecessary separation, and potential duplication and desynchronisation of data. dokieli uses these to compliment the prose but does not rely on them.

This approach also satisfies The Rule of Least Power, proposed by the W3C Technical Architecture Group: when publishing on the Web, you should usually choose the least powerful or most easily analyzed language variant that’s suitable for the purpose.

This allows easy reuse of the content in ways previously unimagined by its original creators [11, 12].

Identifiers

As dokieli documents are published on the Web, they have their own URI. This can be used to refer unambiguously to the document for example in a list of publications by the author, or in indicating the subject of a reply. Further, any individual word, phrase, paragraph, or other subsection of a document can have its own unique identifier using a fragment URI. This enables responses to be targeted very specifically at parts of a document; when additional semantics are applied to relationships, we have the power to create links that say things like ‘I like this concept’, ‘this sentence should be clarified’, ‘this result disagrees with those conclusions’. Within dokieli documents, links can be created to external concepts in the Linked Open Data cloud, aggregating related topics and creating unambiguous references. The dokieli UI provides anchors for all fragments in the margins of a document.

Vocabularies

dokieli does not mandate the use of any particular RDF vocabularies as the content of an article dictates how it is best described. By default, dokieli documents make use of the following; these are replaced or more added at the discretion of the author.

- General-purpose: schema.org

- Publishing and referencing: SPAR Ontologies

- Annotations: Web Annotations

- Social notifications: ActivityStreams and Pingback

- Links to personal storage and user preferences: LDP and Solid

- Access control: WebAccessControl/ACL

Distribution

dokieli application logic, written in JavaScript, is distributed along with every document, ensuring all documents can be edited and interacted with. We consider this a default UI of a document, rather than the required one however, as the data can still be extracted and used in other contexts by other RDF-aware applications.

The progressive nature of dokieli documents is fault-tolerant. If the application scripts or stylesheets are not available, the content is still accessible, allowing continuous utility, albeit in a read-only mode, rather than failing completely. A single document in HTML+RDFa is able to retain all of its core content and semantics without external dependencies.

dokieli is self-replicating, in that the reader of a dokieli document can spawn an instance — either a copy or a brand new empty document — into their own storage space at the click of a button. There is no installation or setup process required to publish content.

Data storage

The owner of a dokieli document has full control and a great deal of flexibility over where to store their article. There are no centralised silos or gatekeepers. However, the capabilities of the system in which a document is stored has an effect on the features which are enabled. At the simplest level, documents can be served from the local filesystem for individual use. To publish documents more widely, they can be hosted on an ordinary Web server, and disseminated with a URL.

dokieli is compliant with Solid, a set of protocols and conventions based on the W3C Linked Data Platform (LDP) recommendation. This incorporates authentication, access control and read and write access to a personal datastore. Hosting a dokieli document on a Solid server allows the author to edit the document directly from a space they control, and grant permissions to collaborators to do so as well. There are a number of open source Solid server implementations already, and users may host their own or choose a provider. There also exist Solid tools and libraries to help developers to build their own Solid-compliant datastore.

An article is the subject of feedback and social interactions such as annotations and reviews. A Solid server can additionally be employed to host these interactions, either in a space owned by the author of the article, or in a more decentralised manner, by allowing a commenter to save their message in their own space. In the latter case, the author is able to configure an inbox on their own Solid server through the dokieli UI, to which notifications of new third-party interactions are sent. These interactions are then displayed alongside the original document, even if the document itself is hosted on a non-Solid Web server, and the article serves as a centrepiece for conversation with as many participants as are inclined to join.

Modes of operation

The core capabilities of dokieli are enabled on a per-document basis, according to the technical resources available for that document. Different combinations of available resources give rise to different modes in which dokieli can operate.

Publishing

Read only: A dokieli instance may be hosted on anything that can serve HTML, including the local filesystem. Content is available without CSS and JavaScript (figure 1). With CSS but without JavaScript, different views are available for consuming media types and devices.

Temporary edit: Hosted on anything that can serve HTML, including the local filesystem. With JavaScript enabled, content may be edited through a web browser and exported to save changes (figure 2).

Local persistent edit: Hosted on anything that can serve HTML, including the local filesystem. Content may be edited through an in-browser JavaScript editor and in-browser Web Storage enabled to persist changes for a longer period (figure 3).

Persistent edit: Hosted on a Solid server, edited through a web browser, with changes saved directly to the server (figure 4).

Data only: Hosted on anything that can serve HTML, content and metadata can be extracted using an RDFa parser and processed, remixed or re-displayed (figure 5).

Interacting

Centralised interactions: A dokieli instance is hosted on a Solid server, with a pointer to a space to store interactions (such as replies, annotations, likes) made by third-parties through the in-browser JavaScript editor (figure 6).

Decentralised interactions: Hosted on a Solid server, with an inbox to receive notifications so third-parties can store their interactions in their own dataspace (figure 7).

Decoupled interactions: Hosted on anything that can serve HTML, with link to a notifications inbox on a Solid server, and third-parties can store their interactions in their own dataspace (figure 8).

Implementation

dokieli is open source and available to try at https://dokie.li/ (or at any instance on the Web). In this section we describe specific features which meet the uses cases outlined previously.

Semantics and linking

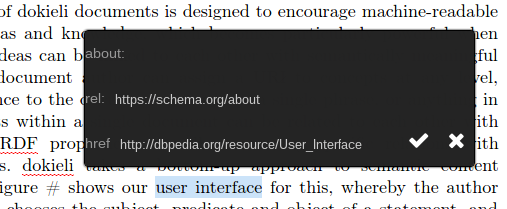

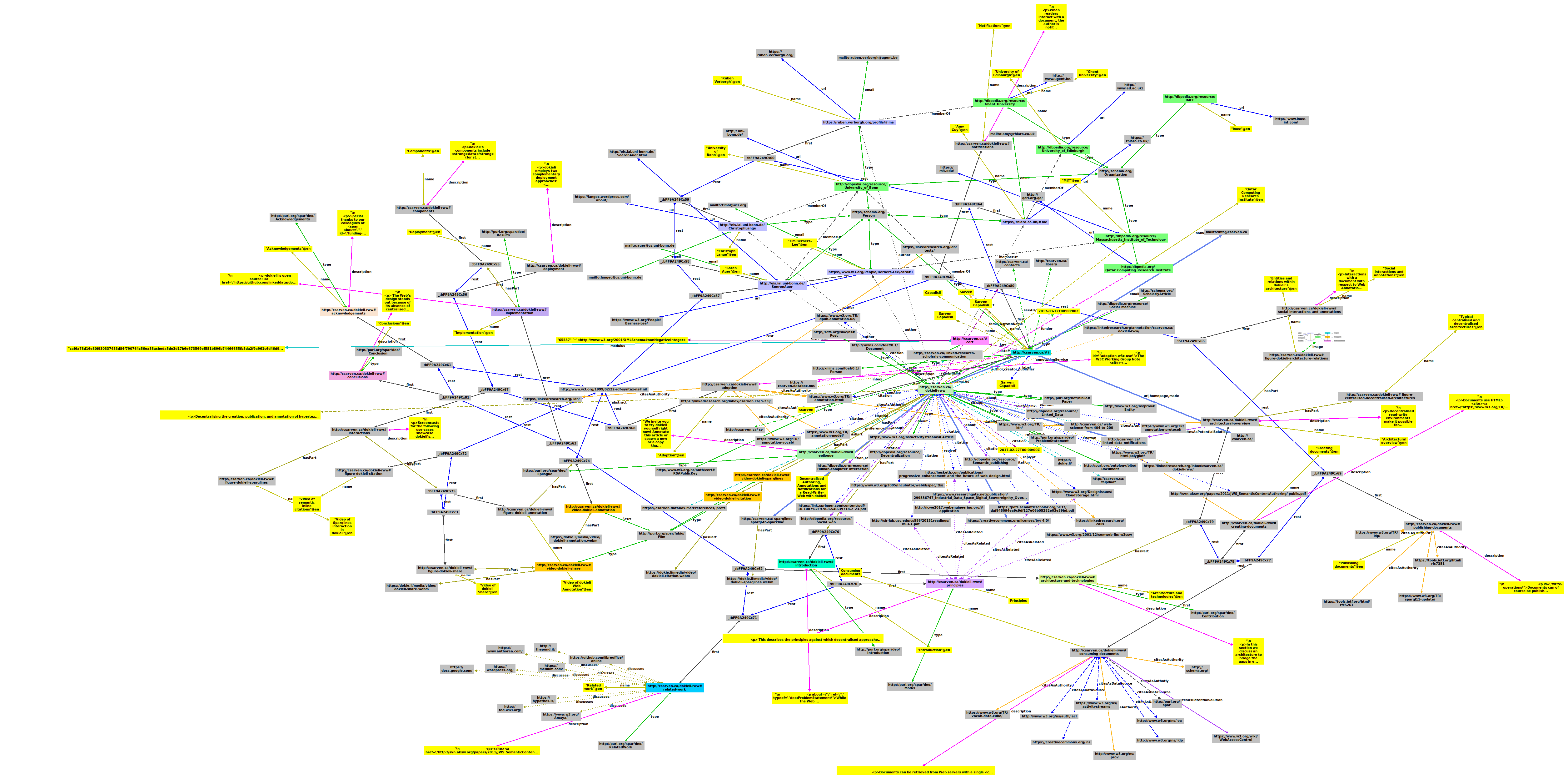

The data format of dokieli documents is designed to encourage machine-readable description of ideas and knowledge, which becomes particularly powerful when these individual ideas can be linked to each other with semantically meaningful relationships. A document author can assign a URI to concepts at any level, permitting reference to the document as a whole, a single phrase, or anything in between. Concepts within a single document can be related to each other with the appropriate RDF properties, as well as creating specific relations with external resources. dokieli takes a bottom-up approach to semantic content authoring; figure 9 shows our user interface for this, whereby the author selects some text, chooses the subject, predicate and object of a statement, and the application inserts the data as RDFa, and if necessary generates a new URI fragment for the subject or object.

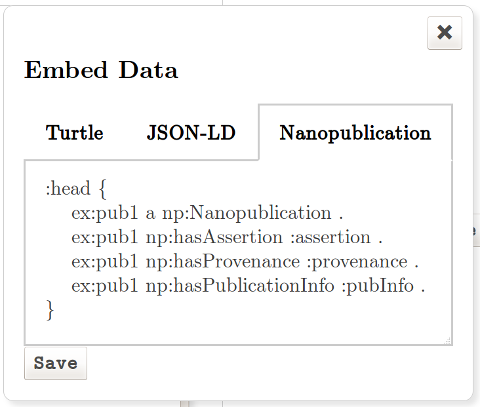

In addition, metadata that does not easily fit into prose (for example, Nanopublications) can be embedded as a single block of Turtle, JSON-LD, or TriG (figure 10).

Figure 11 shows a sample of internal and external concepts and relationships from a dokieli document.

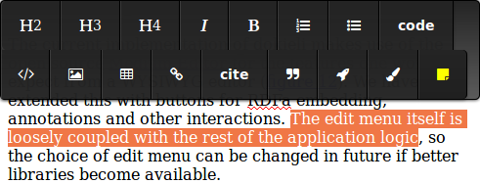

Rich editing

The current implementation of dokieli makes use of the open source Medium Editor for the features one would expect from a WYSIWYG editor (figure 12). We have extended this with buttons for RDFa embedding, annotations and other interactions. The edit menu itself is loosely coupled with the rest of the application logic, so the choice of edit menu can be changed in future if better libraries become available.

Tables of contents, tables, and figures are automatically calculated from the document contents and displayed as in figure 13. The user can also drag and drop here to conveniently re-order sections of the document. Similarly links within a document are automatically compiled into an academic reference list if required by the author.

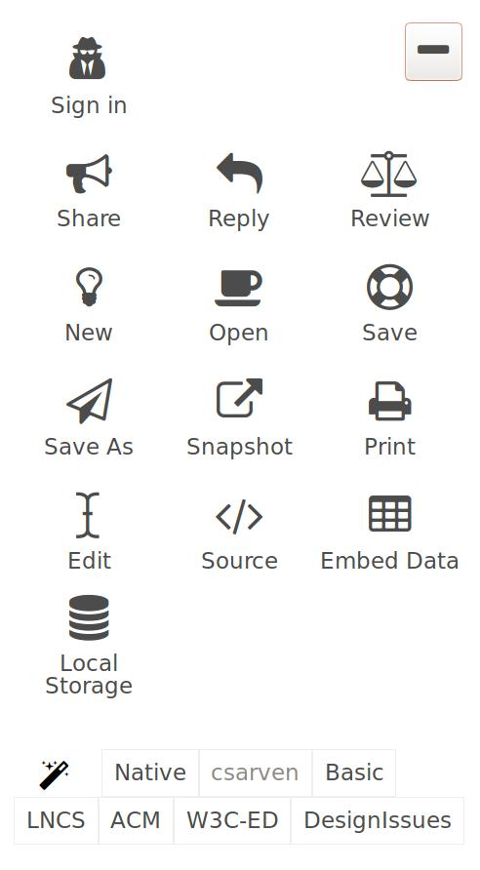

dokieli comes with a number of stylesheets built in, and an author with CSS knowledge can create a new one of their own, or reuse existing styles from elsewhere. It is trivial for the user (whether author or reader of a document) to switch between available views to their preferred one, either through user-agent’s built-in feature or through dokieli’s menu (figure 14).

Authentication and access control

People can identify themselves to a dokieli document through WebID-TLS. Users with a browser certificate installed and a matching FOAF profile containing the certificate public key are authenticated against their own Solid server if found, with a fallback to a known Solid authentication endpoint. This allows the dokieli instance to write to any Solid-compliant dataspace which the user is authorised to write to. This is how users can, for example, save changes to a document, or store interactions such as comments. While dokieli does not currently offer a UI for granting access to collaborators on a document, authors can use other Solid applications (e.g., warp) to manage permissions of data on their server, and thus allow other specific individuals (or the general public) to edit their articles.

dokieli also displays an authenticated user’s name and display picture if available in their profile. In future, we plan to take into account any preferences in a user’s profile, as well as other documents they have previously published, to enhance and personalise the UI.

Storage

Articles may be stored on user’s local filesystem or hosted from ordinary Web servers which can serve static HTML files, for example: university user pages, code repositories, personal or company webspace, or any file hosting.

Articles can be edited in a Web browser, and then exported (figure 15) to save changes. dokieli also makes use of Web Storage in browsers with this capability, which can be enabled or disabled by the user.

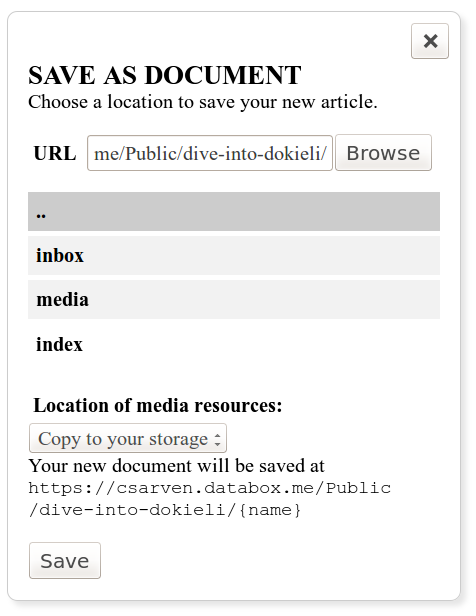

A document stored on a Solid server is readable as a normal HTML page, and additionally editable directly on the server for authorised users (figure 15). The new and save as buttons (figure 15) prompt the user to choose a storage location before generating a blank new document or a copy of the current document respectively. If a user is already authenticated and their profile indicates where to find their a personal dataspace, dokieli presents a dataspace browser, through which the user can click to choose where to save (figure 16). Non-authenticated users may simply type the URL of a storage location they believe they can access, browse the directories therein, and save if the location is publicly writeable. According to the Solid protocol, dokieli uses an HTTP POST or PUT to replicate the HTML+RDFa that constitutes an instance, into the chosen dataspace. The user has the option to copy media and scripts to their own space as well, link to them from a CDN or link to them from the document they are starting from.

Interactions

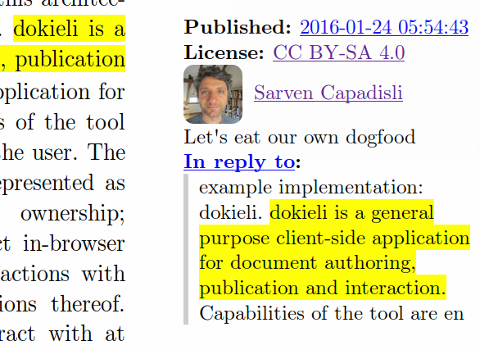

We support the rights of authors to own their data, and store and publish it where they feel most comfortable. This includes the social interactions users make around existing publications. Rather than centralising these interactions around the subject document, we took the decision to default to decentralisation of all content by allowing users to authenticate with their personal dataspace, and choose the location for their interactions at the point of making them. This gives rise to the need for a mechanism to notify the original author that their document has received some interaction. We do this by allowing document authors to specify an inbox for either their article as a whole, or any subsection with its own URI using the ldp:inbox predicate. Inboxes are containers in a dataspace which may be appended to by anyone, and do not need to be on the same server as the document itself; if one article has multiple inboxes they can be distributed across as many dataspaces as is convenient for the author(s). When an annotation is made, dokieli follows the appropriate inbox link and writes a notification there (see figure 17 for this process and listing 1 for notification contents). When the document is loaded, links are followed to all inboxes in order to retrieve interactions there have been notifications about, so that these can be displayed along with the document (figure 18 and figure 19).

Although providing enriched (meta)data is voluntary, provenance level data like the date on which the request was submitted, who by, and its license, can be purposed towards the verification process as well as for displaying. An example inbox notification is shown in Listing [1], in which object is the URL of an annotation, and the target (the conclusions section of an article).

@prefix xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#> .@prefix schema: <https://schema.org/> .@prefix as: <https://www.w3.org/ns/activitystreams#> .@prefix c: <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/> .<> a as:Announce ;as:object <http://example.net/foo/abc123> ;as:target <http://example.org/article#conclusions> ;as:updated "2016-01-24T00:00:00Z"^^xsd:dateTime ;as:actor <https://csarven.ca/#i> ;schema:license c: .

dokieli itself does not offer a mechanism for authors to manage their notifications or choose which interactions appear, as other applications which are specialised for these tasks are under development as part of the Solid application ecosystem.

An author can also opt to allow anonymous interactions with their documents by pointing to a publicly writeable storage location in their own space, and store interactions on behalf of their audience.

Conclusions

In this article we discussed dokieli, an implementation of a proposed architecture for realising a decentralised and accessible participatory knowledge space. By building on existing standards and tooling we contribute towards their ongoing improvement and help to advance the state-of-the-art in user-friendly Linked Data applications, and decentralised social Web technologies. We have shown that native Web technologies coupled with Linked Data enhancements provide a sound grounding for human- and machine-friendly content publishing, and that cutting edge work on personal datastores can be employed on top in a progressive manner. We reiterate that enabling this kind of complex functionality on an as-needed basis serves as a gateway for users and lowers the barrier to entry more effectively than an all-or-nothing approach.

We envision that a further implications of our work is expansion of the missing parts of the LOD cloud on scholarly communication, social interactions, and detailed discourse around ideas and experiences.

Meeting the combination of needs we outlined here comes with many challenges. This is not a new problem, and there are ongoing efforts and initiatives advancing these along various fronts. Having an architecture and tooling in place does not necessarily translate to adoption of technologies or even principles. We have not addressed social, economic, ethical or legal issues around data ownership, decentralised identity or Web applications decoupled from user data. Nonetheless, our efforts iterate towards better understanding of what is needed to improve tooling and user interfaces, so that we may move this area forward alongside related initiatives, and gradually lower the barrier to entry for participation in a decentralised, social, semantic Web.

There is still work to be done. Development is in the open and we welcome you to join the discussion. Our next steps, small and large, are listed as issues on our repository, but we conclude by describing some of the more prominent remaining problems to be addressed.

- Next steps

-

We must concretise a mechanism for adding articles to collections or archives when they are published, for example updating a listing of blog posts, adding new publications to university repositories or sending new works to libraries automatically (issue 38).

Where applicable, scientific processes should be captured in a way that is machine-readable, encompassing workflow and provenance level data. This type of information plays an important role in reproducibility of work, and fostering trust and confidence in results (issues 41 and 119).

In order to improve the utility of social notifications sent and received by dokieli documents, we are considering the W3C Shapes Constraint Language (SHACL) vocabulary to describe the constraints notifications in particular circumstances. This will allow authors to use third-party applications to verify incoming notifications according to their own requirements (issue 105).

There is a growing list of dokieli articles in the wild, that is, researchers taking the initiative to control their work through self-publication. We invite you to try dokieli yourself right now! Leave a comment on this paper at https://csarven.ca/dokieli, or spawn a new or a copy that you can edit yourself. Make it so!

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to our colleagues at MIT/W3C; Andrei Sambra, Sandro Hawke, Nicola Greco, Dmitri Zagidulin, as well as Henry Story and Melvin Carvalho. We are also thankful to collaborate with colleagues at QCRI. This research was supported in part by Qatar Computing Research Institute, HBKU through the Crosscloud project. Last but not least, the contributors to the dokieli code, issues, and discussion.

References

- Nelson, T.: Ted Nelson Demonstrates XanaduSpace, (2013) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1yLNGUeHapA&t=50s

- Evolution of the Web, http://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/Evolution.html

- Capadisli, S.: Call for Linked Research, Developers Workshop, ISWC (2014), https://csarven.ca/call-for-linked-research

- Capadisli, S., Riedl, R., Auer, S.: Enabling Accessible Knowledge, CeDEM (2015), https://csarven.ca/enabling-accessible-knowledge

- Khalili, A., Auer, S.: User interfaces for semantic authoring of textual content: A systematic literature review, Volume 22, ages 1–18 (2013), http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1570826813000498

- Luczak-Rösch, M., Heese, R.: Linked Data Authoring for Non-Experts, LDOW, WWW (2009), http://events.linkeddata.org/ldow2009/papers/ldow2009_paper4.pdf

- Khalili, A., Auer, S., Hladky, D.: The RDFa Content Editor — From WYSIWYG to WYSIWYM, COMPSAC 2012:531-540 (2012), http://svn.aksw.org/papers/2012/COMPSAC2012_RDFaCE/public.pdf

- Volpini, A., Riccitelli, D.: WordLift: Meaningful Navigation Systems and Content Recommendation for News Sites running WordPress, Developers Workshop, ESWC (2015), http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1361/paper4.pdf

- Battle, S., Wood, D., Leigh, J., Ruth, L.: The Callimachus Project: RDFa as a Web Template Language, Consuming Linked Data, ISWC (2012), http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-905/BattleEtAl_COLD2012.pdf

- Jusevičius, M.: Graphity: generic processor for declarative Linked Data applications, SWAT4LS (2014), http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1320/paper_30.pdf

- Principles of Design, http://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/Principles.html#PLP

- Berners-Lee, T., Mendelsohn, N.: The Rule of Least Power, http://www.w3.org/2001/tag/doc/leastPower.html

Interactions

26 interactions

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

This paper describes the dokieli application for document publishing, authoring and interaction in a decentralized way. After introducing the problem space, the whole architecture and the implementation is presented in detail.

The application captures an interesting topic that is often discussed in the academic world. Further, the architecture and the implementation seems to be well thought out. Especially the decentralization and the easy applicability helps the user to adopt the system.

In my opinion, the paper is rather a detailed documentation of the application than a scientific paper. It contains a lot of information, e.g. captured in the 17 figures, that are interesting for the actual user but they are not necessary in a scientific paper. Further, for me it is not clear how the system really differs from existing works, it is only mentioned that other systems are "lacking facilities for linking discourse". A shorter paper focusing on the main aspects and the differences to other systems would be more valuable for the community.

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

The paper presents a client-side application (named dokieli) which allows the semantic authoring (creation and publication) as well as the sharing of documents using HTML+RDFa as baseline technology. The paper comprehensively describes the system and tries to mark down the differences to existing, similar systems like [9] and [6].

In general the paper is more a technical report or system documentation than a scientific publication. I think the interesting parts of this work would have made a great short paper, as e.g. some of the figures are not helpful or necessary to understand the application. In addition, I would recommend the authors to clarify a) their contribution in the paper (what is new and what was reused from other applications) and b) the differences to existing systems, as this is only slightly done at the current state.

Minor Remarks:

- Abbr. LDP is used beforehand but mentioned first in 4.5

- Capitalization of Words within titles (e.g. “Modes *of* Operation” or “Semantics *and* Linking”)

- Captions of figures with or without “.”

- Unification of capitalization of keywords within the text “Listing”, “figure”, …

- Figure 11 seems to be missing

- Within the online version of the paper (scarven.ca/dokieli) 4 authors are listed

- Affiliation of Author1 is incomplete (*I*nformation Systems …)

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

This paper, presenting the architecture of the open source implementation dokieli, is of high quality, well structured, and written in a clear and understandable manner. The implementation demonstrates the high potential of the concepts described in the paper and is an innovative approach for collaborative editing, semantic annotation, and publishing/share structured texts (e.g. articles).

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

The present work describes a client-side application for "decentralised authoring, annotations and social notifications". It is a particularly relevant work as many academics could benefit from a better tooling support in scholarly writing, debating and publishing.

The paper describes in much detail the many features of the tool. Some requirements include user-friendliness, decentralization, or progressively enhanced functionality. Other ideas presented in the paper (e.g. the annotation of Web pages) have already been published by the same author(s) in the past. These features altogether contrast the proposed architecture from established tools for content editing and publishing like Google Docs or Authorea.

However, despite of the rich feature set, there is no evidence in the paper that the mentioned requirements are fulfilled by the tool. It is described that the application is built on existing tools like a rich editor, and it is complemented by a mechanism that allows to host data on a private datastore for privacy. But an evaluation e.g. in the form of a user study is highly missing to make this a sustainable scientific work.

Compared to previous publications of the author(s), I cannot identify many novelties that make this scientific work sufficiently distinctive. It looks like a natural evolution of previously published research [1] with some additional features. Maybe the main focus should be shifted more towards the core additions, like the possibility to set up personal data spaces with access control, interaction, and notification. Still, the benefit compared to online editing platforms needs to be made clear.

From a readability point of view, it appears that some statements are repeated several times. E.g., 4.5. Data Storage and 4.6 Modes of Operation could be combined into a single heading. Generally I think that the paper could be made much clearer by some simple restructuring. I found also the introduction a bit difficult to read, esp. as it deviates a bit from the common academic writing style.

Provided the limited scientific novelty and the weaknesses outlined above, my recommendation is a weak reject for this paper.

[1] This ‘Paper’ is a Demo, ESWC 2015 Satellite Events.

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

Meta-review:

Taking into account the balance of other reviews, I recommend rejecting this paper on the following grounds:

- A need to rewrite the paper to fit a more typical scientific narrative/tone.

- A need to provide stronger analysis of the relationship to previous/related work.

- A need to provide greater clarity of the scientific contribution.

- A need to more clearly demonstrate the delta over previous work.

The outcome aside, I would like to highlight the positive comments of the reviewers on the value of the work, and the likely interest to the community, and would encourage the authors to resubmit to a related conference/workshop or a future LDOW once these issues have been addressed.

Amy van der Hiel W3C replied on

interesting. dokieli for decentralised authoring, annotations and social notifications https://twitter.com/csarven/status/697810297080442880

Stian Soiland-Reyes replied on

Stian Soiland-Reyes replied on

(My review was also posted at https://gitter.im/linkeddata/dokieli?at=56bdd64ffa79226456f9eda8 )

I must admit I agree with the meta-review, I think the reviews are fair in that the article reads more like an Application Note or technical report, and would benefit from a stronger evaluation and justification of its novelty.

I don't think details like the flow diagrams are needed, also the pretty publishing mode pictures feel out of place . The technical work seems sound and very promising - this kind of move towards collaborative and distributed easy-to-use semantic publishing is exactly what is needed to revive academic publication for the 21st century.

I would have appreciated a stronger focus on *provenance* and attribution, e.g. FOAF is mentioned - strong identification of authors should be even more important in a distributed model, so I would have expected some relation to ORCID - which RDF representations provides FOAF and PROV descriptions of people (and currently planning integration with SPAR ontologies).

Similarly *versioning* is not mentioned, and a dokieli paper that is published online in a distributed manner (possibly even at multiple locations) and subject to collaborative editing would naturally have many different versions (e.g. pav:hasVersion), which could make it hard to cite which version has actually been reviewed, published, updated, etc.

It would also be important to relate these versions to each-other so you could know when to talk about the "same paper" in a more abstract sense, as with prov:specializationOf or SPAR FaBiO's use of FRBR relations between Work/Expression/Manifestation/Entry - this would particularly become relevant when a dokieli paper is accepted by a more traditional publisher which assign it's own DOIs and republishes the text (the Expression) in a slightly different Manifestation (probably breaking most of the RDFa links) at a different Entry (new URL).

One strong argument for semantic scholarly publication is that you have the possibility to break down the strong barrier between the article text and the traditional supplementary material, as you gain the possibility of a closer integration of data and visualizations from within the dokieli article - as the author has previously shown. One big challenge here is that the boundary of the article becomes blurred - some kind of aggregation of resources that constitute the article in the form of a research object or similar would help to mark out what is the scholarly unit that is actually being proposed for review, publication and citation - and also to help attribution-wise as you can break down what authors contributed where.

Christophe Gueret replied on

Christophe Gueret replied on

This system paper describes a flexible solution for concurrent editing of documents. Contrary to the leading centralised models of on-line editing the solution can be deployed in a decentralised way and cope with local and server-based scenarios. It is also entirely based on Web technologies and standards, making it a truly open platform everyone can easily build tools around.

The system is compared to things like Google Docs but my understanding is that concurrent real-time editing is not supported at the moment. This could be stated more clearly in the paper and some future plans for implementing it should be introduced. I'm especially curious how the authors will deal with editing conflicts in a decentralised and asynchronous deployment setting.

Myles Byrne replied on

Myles Byrne replied on

I took a good look under the hood of projects such as eLife Lens and Composer, and its newest imitator Manuscripts, but felt an underlying disappointment that none of these reached the needed level of accessibility, openness, and semantic design for true open and citizen science. Indeed, Manuscripts goes in the wrong direction. Diving into dokieli and SoLiD, i had at last the feeling of 'this is it': after decades of struggle to realise a usable semantic web platform, a breakthrough!

In turn, i disagree with the reviews of this paper calling for rejection (perhaps to a Kuhnian extent). The grounds given for rejection seem forgetful of the lessons learned from the 2+ decades of struggle to get here. The rough edges of the paper are appropriate given the nature of the medium addressed (the web). Dare i say it: with dokieli, a bit of the magic of first writing HTML in NCSA Mosaic in 1993 is coming back. To go along with some of the grounds given for rejection of this paper as a scientific work, would be to move backwards in terms of web science, HCI, and related (e.g. Tuftean) concerns.

In contrast, and in agreement with the authors, i feel salient issues to address fall under the category of progressively enabling dogfooding/usability for a widening population of researchers and social web users. At this early stage, an appropriate criticism seems to be that Dokieli is not yet a practically functional editor - for now, HTML5 + RDFa still need to be at least partly coded separately. Dokieli seems to be navigating into a new space that hybridises elements of static site generators, collaborative document editors, and faceted LD browsing, integrated with a decentralised social LDP (SoLiD). Is it an antipattern, then, to keep switching from dokieli into Warp to directly edit the HTML? Should text editors integrate into a dokieli / Linked Research workflow?

Ruben Verborgh replied on

Ruben Verborgh replied on

Dear authors,

What is the goal you would like to achieve most with dokieli?

How do you imagine it changing the world?

I’m asking because I think the work itself is exciting, but I’m unsure whether the channels you are using really help you achieve your goals. Is your goal really a publication at a workshop? Probably not… I’m quite sure you have higher ambitions, and that a publication is just a stepping stone toward something bigger. That said, are you sure a scientific publication is the most efficient stepping stone to reach that goal? I think not. And that’s probably the wall you’re hitting and will keep on hitting. You might be picking the wrong battles.

The anonymous reviewers ask for science—I can’t blame them, given the type of venue you are submitting to. I saw some comments pass by on Twitter that approached this focus of the reviewers in a humorous way. That’s totally fine, but know you can’t blame the reviewers for not accepting this work. Their reviews reflect fitness for purpose, not an absolute judgement of quality. I believe the work was indeed not fit for the particular purpose you chose it for.

Let me be clear and frank: what you are doing is not science. And it shouldn’t be. Not being science is not a quality judgment. Art is not science. A good novel is not science. A marvel of engineering is not necessarily science. That doesn’t make it any less useful. It just makes it unfit for scientific discourse.

On the engineering quality of the work, I have few comments. It’s a great solution with appropriate technologies. A few minor issues that come to mind:

- What exactly is dokieli, and what is an instance? Is it a document, platform, both?

- Why do you ship the application logic with the document (and what is the document)? Why not ship the document without code, and have an external UI? You hint at the possibility of this in the text, but this is not detailed, while I think it is an important point.

- Is the fact that RDFa does not support graphs a limitation, for instance, in the context of Nanopublications that typically involve graphs? What languages should a client of dokieli documents understand?

- I have some concerns about novelty, with regard to things such as identifiers, data storage, etc.

On the science aspect of the work, I have much more comments. I could not talk about this, because I know it is not how you like this contribution to be evaluated. But if you submit to a scientific venue, I feel I must comment on this.

My main issue: what is the problem? Despite the presence of a “Problem space” section, the entire document is structured as a “nice to have” rather than a problem that needs addressing. I’m not saying it isn’t nice, but “nice” doesn’t necessarily make a nice research paper. It starts with the abstract: you describe feature after feature, without arguing a need for them. You first need to convince me there is a problem before I can possibly start caring about it. The introduction continues this line of reasoning. Yes, Nelson is right that we imitate paper. So what? Why is paper so bad? Does paper lead to high costs? Does paper lead to a worse understanding? Missed opportunity doesn’t really result in disaster. The same holds for the evolvability argument. Why is evolvability important? What happens if we don’t do this? You believe that your solution “has the potential to both proliferate high quality machine-readable data, and enhance human-friendly knowledge sharing on the Web”. Why is that necessary? What is wrong with the ways in which we currently share knowledge on the Web?

Research starts from a problem. One presents a solution that addresses this problem, measure how well it addresses that problem in comparison to other solutions. This allows other people to improve upon one’s solution (and measure to what extent they do so). Exploring feasibility is not science. The Semantic Webber’s Guide to Evaluating Research Contributions (PDF, sorry) calls this “look, ma, no hands!”. It’s not research if you cannot fail. How do you know if you have been successful? How can you measure this? Why is your solution a good solution? What does my solution have to do to make it a better solution?

If you want my opinion, don’t try to be science. Don’t do it. You’d be fighting the wrong fight.

If you’re on a mission to make this way of publishing the default way, you have my support. But competing with research papers is not something you need to succeed with that mission. Trying to turn this into a research paper will weaken the contribution that you have. There’s nothing to measure here—and nothing to gain from that.

If you do want to turn this into a research paper, you’ll need to have a clear research question, a clear way of failing/succeeding, and a measurable way for others to improve upon what you build. But again, does this contribute to the eventual goal you aim to reach?

Finally, a wholly different kind of remark: the user experience. Please forgive my bluntness—I know that taste is subjective—but I found the aesthetics so poor that they really distracted my reading. A brownish background with a large sans-serif font does not provide me with a superior reading experience—which is the least I would expect from a project that aims to improve upon paper. There are various design flaws that make this text highly unpleasant to read, and that’s bad marketing. A couple of examples: I need to scroll 2 full screens until I get to the meat of the paper. Why do the author names and affiliations have to take an entire screen? There is a table of contents, but it is hidden behind a menu button (despite there already being a menu). The contrast is too low for pleasant reading. The drawings are too large and disconnected. The mobile experience is highly fragmented. I suggest to take a close look at the typography of sites like Medium, National Geographic, and Wired. Right now, you’re ignoring your most numerous audience: there will always be more reading than writing.

My advice for going forward would be to clearly identify your goal, and ask yourself what the best way is to reach it. Rejection of this work does not prove anything (right or wrong) if it is sent to the wrong place. Pick your battles. Fight only those you need to win. Don’t let the others distract you.

Best,

Ruben

3 interactions

Alvaro Graves replied on

Alvaro Graves replied on

This is an interesting and valuable tool. I believe there is a critical need for more tools like this, especially in Semantic Web and Web Science communities, that are averse to eat their own dog food.

However, I find it hard for this publication to be accepted on a regular venue, given its lack of hypothesis, methodology, etc. This is a problem in general when presenting new Semantic Web tools that are not considered "new scientific contributions", something I disagree completely.

I would like to see some linking from newly spawned instances to the original ones, maybe using PROV-O or other provenance vocabulary. I think linking the "ancestry" of an article is critical to enable a richer discussion. Apparently this can be done manually (via RDFa), but I don't think that is a good approach.

Figures 2 and 3 are confusing IMO

The link showing a growing number of articles shows an empty list.Fixed

I'd like to see a further discussion on what are the plans to test Dokieli in real environments. I can imagine three levels of testing: (1) use of Dokieli among SemWeb researchers as a minimal (2) IT/CS researchers and (3) scientists in general. I think the needs and abilities of each group will lead to changes in the approach Dokieli has taken. For example, it is not clear to me that non-SemWeb people are interested in adding RDFa annotations. If that is true (and this is just an hypothesis), how can we encourage them?

I think one of the most valuable aspects of Dokieli is the potential ability to include research data and other supplementary information, such as code. Although implicit, the authors would make a stronger case if they mentioned this particular use case, that I believe is critical in science. For example, it would be really interesting to be able to link papers to datasets, visualizations, iPython/Jupyter notebooks or other web-based data toolboxes.

Another missing discussion is about versioning. Even if it is not directly related, many of us do use git+latex or other combination of tools for collaborative editions that allow version control. Apparently this is not addressed by Dokieli.

Minor issues:

- CSS doesn't seem to work properly. I can't see any change when creating a H2 element.

- The authors forgot to mention Google Docs as a de facto standard collaborative tool on the Web that allows annotations.

- Menu on title appear too high and can't be used.

- There is no clear way to mark RDFa for the whole article.

- The RDFa option also forces me to copy and paste whole URIs. I can' imagine some service that provides autocomplete that could be useful for 90% of the times I want to add metadata this way.

- As any WYSIWYG editor, things can get really messy when inserting, deleting sentences in the middle of a paragraph. It would be nice to have a Markdown mode or something equivalent.

Vladimir Alexiev replied on

Vladimir Alexiev replied on

@csarven's #dokieli the future of #linkedresearch and #sempub scientific publishing? csarven.ca/dokieli @force11rescomm Beyond #pdf

Alf Eaton replied on

SOLID data storage, Linked Data Notifications; several interesting things in @csarven's dokieli dokie.li

Jaime Jimenez replied on

IMO researchers should move towards #linkeddata and dokieli: github.com/linkeddata/dok… . Kudos to @csarven and all who made it possible.

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

Since the page count greatly exceeds the maximum specified in this year's CfP, I must recommend to reject the paper.

This is unfortunate, since the dokieli system appears to be very interesting. Therefore, I would encourage the authors to rewrite the paper and resubmit it in a relevant conference.

At the same time, I would also strongly suggest to include a more comprehensive discussion of the advantages of this solution (e.g., which are the specific limitations that the system will address? How will it impact the users in term of usability? How does it improve on the state of the art?) and –crucially- an evaluation, since at the moment the paper presents no empirical evidence of the benefits of dokieli.

In general, most of the issues flagged by previous reviews at https://csarven.ca/dokieli still appear to be unresolved.

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

The dokieli tool is nice, well designed and implemented, and surely worth presenting to the community.

Though I do not think the research track is a good place for this kind of paper. It can be a very good poster instead. In fact it is actually a (detailed) technical report on the system, more than a research paper.

The requirements of the system are just listed in Section 2; a more detailed explanation of the process to derive them is needed. The paper should better frame the problem being addressed and the contribution.

The related works section is also just an overview of tools and does not identify the specific problems addressed by this work. The paper should also compare the proposed solution with the existing ones.

Section 4, and especially section 4.2, just lists some architectural choices, without really justifying them.

A lot of details could be removed from the implementation section; some screenshots could be removed as well.

The discussion is rather short, some end-user tests and usability evaluation is needed to demonstrate the robustness and applicability of this work.

The authors made available past reviews on this paper, most of which raised similar concerns, but they haven’t addressed these concerns yet.

A minor point: a lot of tools, libraries and technologies are mentioned in the paper but some references are missing (to websites, repositories, specifications).

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

The paper is 20 pages long. According to EKAW2016 call for papers:

"All submissions for research, in-use and position papers must be in English, and no longer than 15 pages. Papers that exceed this limit will be rejected without review."

The paper fails to fulfill the length requirement.

From a content point of view, the paper presents a very interesting approach/tool for document authoring, publication and interaction. I believe it has the potential to change the traditional way authoring and publishing is currently done. It truly shows how Semantic Web technologies can be used to create a collaborative and distributed apps.

Although the work itself is very interesting, the way it is presented, as a scientific publication, has many problems e.g. the problem addressed is not clearly defined, there is no methodology, and no evaluation.

Sarven Capadisli replied on

Sarven Capadisli replied on

This image will be updated from time to time to include the changes, e.g., social interactions, on this resource.

Ali Khalili replied on

Ali Khalili replied on

is there any plan to also address 'user adaptation' in dokieli? in particular I am thinking about multilingual content as well as other types of customization/personalization based on the context of user who reads a dokieli document.

1 interaction

Sarven Capadisli replied on

Sarven Capadisli replied on

There are some issues in the dokieli repository (see along the lines of user/application "preferences", "configurations", "settings", if I remember correct)..

There is no working solution at the moment. The idea is that users come to use dokieli with their preferences (e.g., declared somewhere in or near their profile), and dokieli will adapt to it.

I've created https://github.com/dokieli/dokieli/issues/172 to track this feature better. Thanks for raising this.

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

This paper presents dokieli, a decentralized web-based authoring service.

The paper is very well-written and a pleasure to read. The service presented here is nice and useful, it defines a new way of publishing and interacting with content on the Web. There are many on-line resources that can be triggered to understand more about this service; indeed, the reader can access the github repository to gather more information and also the dokieli Website is a useful resource. Nevertheless, the paper itself does not provide many technical details and remains quite at a high level.

The contribution is well-suited for the conference and it should generate interesting discussions at the conference.

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

The authors present dokieli, a decentralised, browser-based authoring and annotation platform to create “living” documents that are interoperable and independent of dokieli. Dokieli follows standards and best practices, mainly HTML+RDFa for, Linked Data Platform for personal data storage, and Linked Data Notifications for updates. The presented platform has real potential in the context of academic/journalistic writings. The paper presents good arguments around the use of such a decentralised system to offer authors ownership and sovereignty over their data. The implementation is also sound. However, the paper lacks rigour from the perspective of comparing work against existing approaches. The authors do compare and contrast their system with other offerings; however, the research work and techniques used by other is not critically analysed (for example, there are almost no references in the main text. However, there is an excellent list of references at the end, was this intentional?).

Anonymous Reviewer replied on

The authors illustrate a decentralized framework for web-based authoring and annotation service.

The paper is really well-written, organized and motivated.

The main weakness is the nature of the proposal more fitting a demonstration context rather than an application/industrial scenario.

However the contribution will leverage a fruitful discussion during the conference.

Social and Technical Impact

We identify data generation, ownership and reuse to be key areas of potential impact. Whilst dokieli is still very much a work in progress and the real impact is uncertain at this stage, we use these as a guide to inform our future direction.

Data generation

Semantic structure in prose content is somewhat difficult to capture, and as a result the Linked Open Data cloud is lacking in data about knowledge and ideas expressed in this form. It is especially alarming that this is even the case for scholarly communication in Web science. Through automatic insertion of RDFa into articles and social interactions, and integration of a semantic annotation UI into a generic authoring application, we hope that a side effect of dokieli use will be an influx of previously uncommon but highly valuable Linked Open Data into the Web. Mining, reusing and remixing this data has the potential to give rise to new threads of conversation, connections between and perspectives on ideas and experiences. We are focussing on scholarly communication as a forum for encouraging knowledge sharing with dokieli through the Linked Research initiative, as an area in which augmenting content with machine-readable semantics can really improve knowledge transfer to benefit researchers.

Data ownership and reuse

Having more control over one’s personal data brings a number of potential, though as yet not necessarily properly tested or fully understood, advantages. We advocate at least for having the option to choose which organisations or individuals hold and have access to personal data, and thus argue that our progressive approach to participation at least serves as a starting point to lower the barrier to entry for data ownership.

We believe a particular strength of the Linked Data approach is that data produced with dokieli is reusable by other applications, and easily integrated with data from other sources. Our work is towards encouraging an ecosystem of applications which are decoupled from user data, discouraging vendor lock-in as services must compete for user attention by providing value rather than hoarding information.